Part 7. Sold Again

Nathaniel Ware and his wife Sarah moved to the town of Washington, near Natchez in Adams County, Mississippi. They continued to own and profit from the Woodville Plantations just 30 miles south.

Terry Alford’s book Prince Among Slaves: The True Story of An African Prince Sold Into Slavery In The American South, tells the story of Abdurahman Ibrahima, an African Muslim, son of the Almami Ibrahima Sori – Commander in Chief of the army in the Futa Jallon town of Timbo, Guinea, West Africa. Abdurahman, at the age of 26, was taken prisoner in a war between Futa Jallon and Kaabu around 1788. He was sold to Thomas Foster, a plantation owner in Natchez. After being enslaved on the Foster plantation for 38 years, Abdurahman managed to negotiate his release on the agreement that he return to Africa and not live as a free man in the United States. The book tells the story of how the Natchez newspaper printer and publisher, Andrew Marchalk, provided an escort to travel with Abdurahman – first to Cincinnati, then to Washington D.C. where he met with the U.S. President, and on to Philadelphia.

The escort Marchalk had arranged for the trip was Nathaniel Ware, a planter and once acting governor of Mississippi. Ibrahima had known him for ten years as a neighbor of Thomas’s. He was a handsome person, fair-skinned, with long, thin hair that fell onto his neck. Ware was selling his Mississippi farms and moving himself and his daughters to Philadelphia. His domestic life at Natchez had been shattered when his wife, Sarah, went insane at the birth of their second child.

Nathaniel Ware’s wife, Sarah Percy Ellis Ware, who inherited one-fourth of the Charles Percy Estate and enslaved families, and one-third of her husband John Ellis’ Estate and enslaved families, also inherited the Percy mental illness.

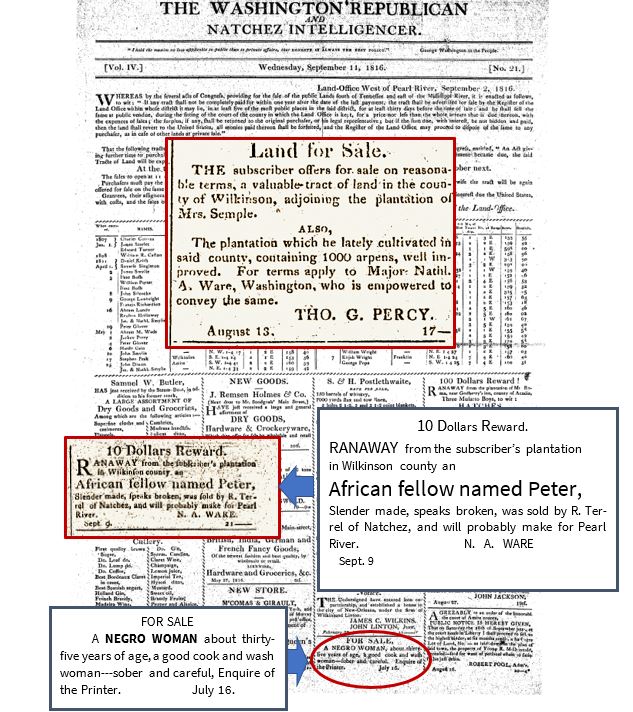

In Prince Among Slaves it states, “Ware had long had an interest in Africa, and he held Africans as slaves on his plantations. He would later travel on the African continent.” In the September 11, 1816, edition of Andrew Marchalk’s newspaper The Washington Republican and Natchez Intelligencer, Ware placed an ad offering a $10 reward for the return of Peter, an African “fellow” who was sold to him by R. Terrel of Natchez. Peter, in the never-ending spirit of African resistance, had run away from the Plantation.

(In the same September 11, 1816 edition of the Natchez Intelligencer, an ad is placed by Andrew Marchalk – the printer and publisher of the newspaper, selling a “Negro Woman.)

Ware, who described himself as “a planter of cotton and owner of slaves,” wrote Notes On Political Economy As Applicable To The United States. In the book he discusses the United States chattel slavery and plantation economy and gives a stark view of the conditions of the Black enslaved families on his plantations in Woodville. He writes.

The slaves live without beds or houses worth so calling, or family cares, or luxuries, or parade, or show; have no relaxations, or whims, or frolics, or dissipations; instead of sun to sun in their hours, are worked from daylight till nine o’clock at night. Where the free man or laborer would require one hundred dollars a year for food and clothing alone, the slave can be supported for twenty dollars a year, and often is.

… A slave consumes in meat two hundred pounds of bacon or pork, costing in Kentucky, Ohio, Indiana, Illinois, Missouri, Tennessee, and Western Virginia, $8; thirteen bushels of Indian corn, costing $2: this makes up his food. Now for salt and medicines add $1, and it runs thus: a year’s food is $11. Their clothing is of cottons—fifteen yards Lowell, $1.50; ten yards linsey, $4; one blanket, $2; one pair of shoes, $1—making $7.50. Now this sum of $18.50, say $20, divided among the working days, is six cents.

Ware, and the Mississippi plantation slaveowners, constructed a life for our enslaved families so they could work 16 hours a day in the cotton fields – roughly August to December, with only enough food, clothing, shelter, and medical care to survive. Further, the goal was to strip away any sense of personhood, or “family cares,” or memory of life before enslavement. This was the life designed by the plantation owner to maximize profits by controlling the minds and bodies of the enslaved.

Inside the cabins, the families continued to grow. Most found ways to hold on and take care of themselves and their families. Some, like Peter, ran away.

After the death of Sarah Percy, Ware sold the plantations, cashed in on the windfall profits, and later moved on to Philadelphia and then to Waco, Texas.

Next: Dr. J. C. Patrick of Edgefield South Carolina – The Last Owner

Mr. Blakes,

I enjoyed reading the chronicles of the enslaved at Edgefield but this latest one is amazing especially with the amount of food calculated for each slave along with the toiling in the field for long periods of time.

Marlene thanks for reading.

Mr. Blakes, this is a wonderful example of how the details aren’t lost to history. That’s the tale and I suspect part of the whitewashing and brainwashing. Thank you. Your hard work and attention to details give all of us hope. Excellent work.

Thanks Brenda.

Alvin,

I am in awe at the attention to details in the budget of the enslaved on the plantation. Your research continues to open my understanding of the life lived by my enslaved ancestors.

Thank you!

Vernita

Vernita, thanks for reading.

Wow! What a vivid description of the resilience of African slaves! Thank you for the descriptive read! It’s so important to envision the humanity of our ancestors and admire the strength and courage it took to endure the time! Because they did….then came us! I enjoyed the fascinating read!

Thanks for reading Gwen.

Another phenomenal blog post! Thanks for posting the newspaper ads along with the detailed list of the minimal amount of money spent for food, clothing, medicine, etc. for the enslaved. Our ancestors had a fortified spirit and will to live to have survived the circumstances and treatment which they encountered. Thanks for enlightening us with the historic details.

Thanks for reading and commenting Deborah.

Thanks Mr. Blakes for your meticulous research. As Brother Malcolm would say “make it plain’ so we cannot avoid knowing just how inhuman and ruthless these so called businessmen/women were.

Thanks for reading Ms Clark.

I love reading these series. I’m sure I have read this post previously, but I wanted to read it again. I then thought I would look at my DNA matches again to look at my Foster matches. I knew I had matches that had the Prince in their trees, but I wanted to re-visit this after reading this post. My 1st cousin, who had not taken an Ancestry test before also came up as a match to someone who has Abdurahman Ibrahima in their tree. My paternal side lived in Adams/Leflore/Washington/Wilkerson County, MS. I will do more research and see what other trees look like. Keep up the good work.

Thanks for your comments Gerri. In the book Prince Among Slaves it mentions Abdurahman knew Nathaniel Ware, the owner of Edgefield Plantation who lived in Natchez. So far, I have not heard of any DNA matches from Wilkinson County.

The prince still has family in Wilkinson County. He was given the name ‘Prince’ and has several descendants named ‘Prince’. His g-g-g grandson, give or take a ‘g’ is my uncle by marriage. My uncle-in-law, his son, and his dad are named for Prince Abdurahman . Prince Collins is their name.

Is this all you have to say about Nathaniel A Ware? I am just curious. You ever read his book

Notes on Political Economy by a Southern Planter. Have you not noticed the difference between the kinds

pf slave owners were there? Or do you just class them in one grouping.