Noland Veal was born around 1847 on Holly Grove Plantation in Centreville, Wilkinson County, Mississippi. He was the fifth child born to William Veal and Mary Brent. He married Milly Wright around 1865. Milly was born in 1852 in Mississippi. Her parents were Edmund Wright, born around 1820 in Virginia, and Marie Sims, born around 1835 in Mississippi. Together they had 6 children; Julia (1870), Preston (1874), Florence (1876), Wright (1878), Benny (1880), and Matoka (1884).

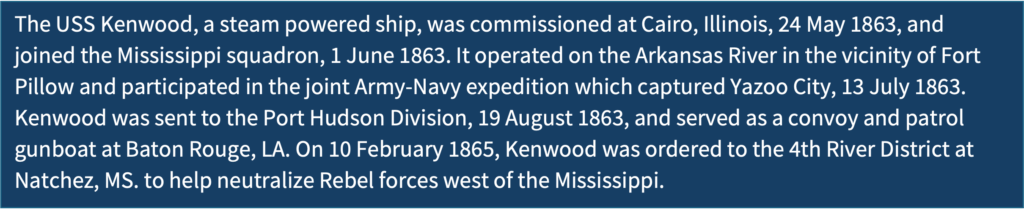

On 2 March 1864 Noland Veal, at the age of 17, ran away from enslavement on Holly Grove Plantation and enlisted as a “1st class boy” on the USS gunboat Kenwood. Noland, his cousin Richmond Veal and several others from Woodville area — Washington Farrar, William Bell, Edward Sims, and Sterling Dumars, Andrew Hayden, George Washington, Wills Martin, and William Bladen, were mustered in aboard the Kenwood on 31 March 1864. The Kenwood was stationed at Bayou Sara, Louisiana, a small Mississippi River port town controlled by the Union forces in West Feliciana Parish, Louisiana. Bayou Sara was just south of the state line across from Wilkinson County, Mississippi, near present-day St Francisville. After repeated flooding the town of Bayou Sara went under water in the flood of 1927 and is no longer there.

As a 1st Class Boy aboard the Kenwood, Noland reported to older seamen and had various tasks around the ship, including cleaning, maintenance, and carrying messages, assisting in the operation of the ship’s guns during battles fetching ammunition and helping to load the gunboat’s cannons. The term “powder monkeys” was used in the Navy for the young boys who fetched gunpowder for the guns. In addition, Noland had the task of helping to spot Rebel ships, look for hazards in the shallow parts of the Mississippi river, and to help look for snipers on the river banks.

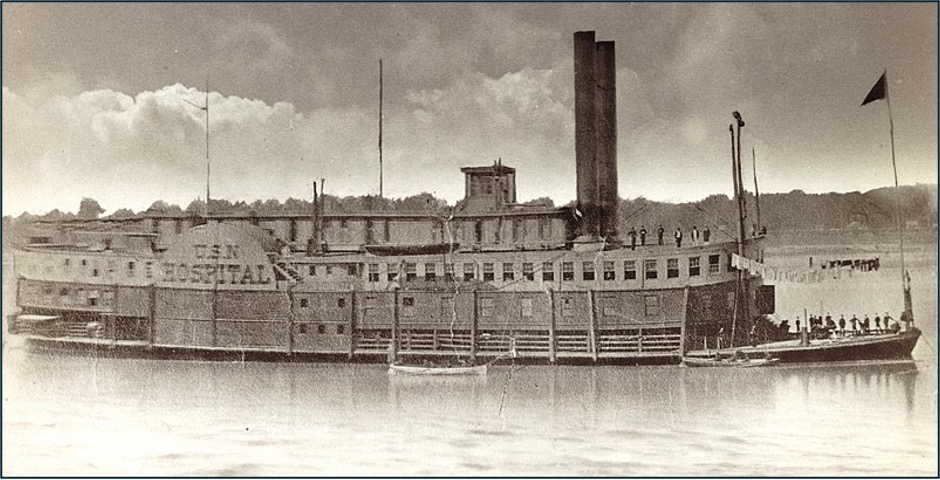

On August 3, 1865 Noland (Viel) Veal is recorded in the U.S. Naval Hospital Tickets and Case Papers, 1825-1889 as having been admitted as a patient on the US Naval Hospital Red Rover, a Confederate States of America steamship that the United States Navy captured and used as a hospital ship during the American Civil War. His military records show him in service on the Red Rover but he was likely just a patient on the ship. Noland Veal was discharged from service in 1865 and returned to Wilkinson County.

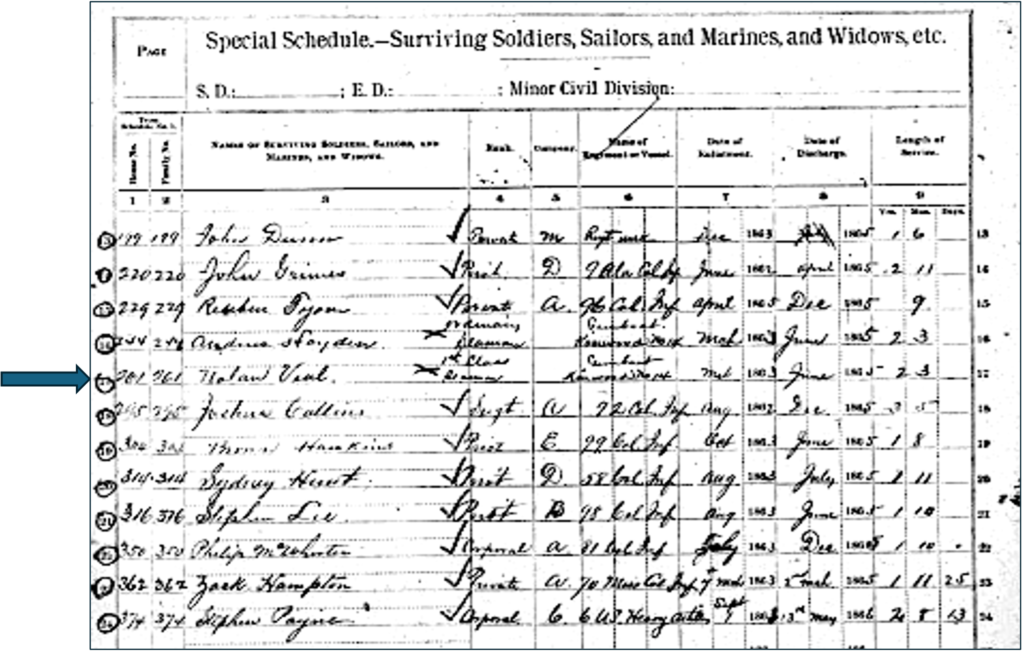

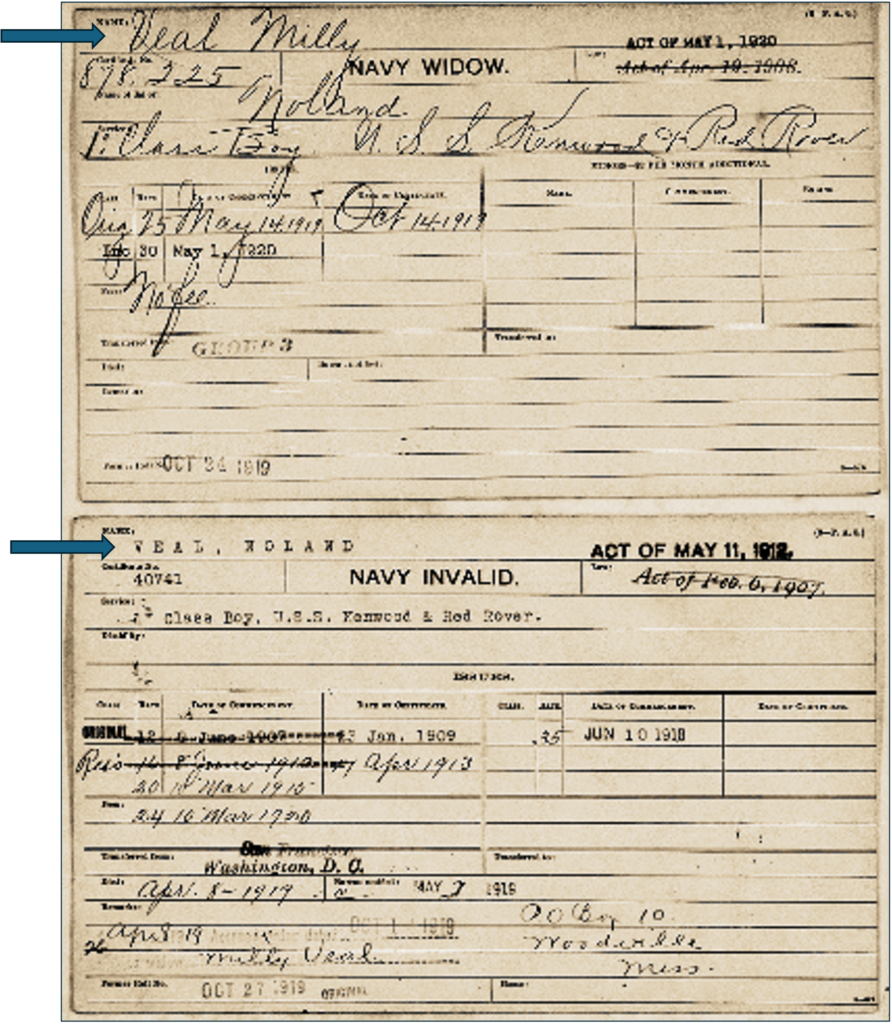

In the 1890 Wilkinson County Veterans census Nolan Veal, Andrus Hayden, and William Bladen, all lived in Wilkinson County and are listed as having served on the USS Kenwood. In the 1900 census, Noland was a sharecropper in the Cherryfield community in Wilkinson County and owned his own home. Although I have not located his pension file, he filed for and received his pension beginning 24 February, 1909. His pension payments started out at $12 per month and increased to $35 per month by the time of his death in 1919.

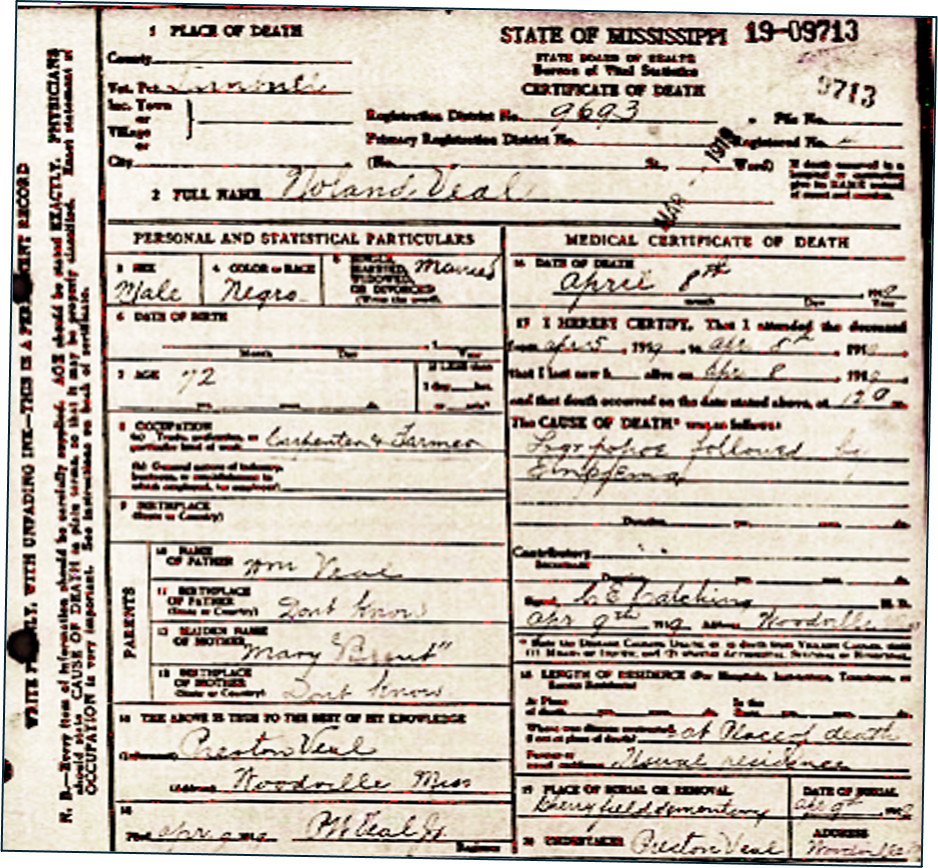

Noland Veal died 9 April,1919, at age 72. I wrote about him in an earlier blog as one of the Veals who died in the midst of the 1918-1920 H1NI influenza virus pandemic in Wilkinson County, Mississippi. He was buried at the Cherryfield Cemetery in Woodville, Missisippi. After Noland’s death in 1919 his wife Milly filed for and received her widow’s pension. Since the Civil War Navy was not segregated by race, the names of the 18,000 Black Navy veterans like Noland Veal are not recorded at the African American Civil War Monument in Washington, D.C., but, I am told, the names will eventually be added to the monument.

Most notable among Noland and Milly Veal’s children was their son Preston, who was my mother’s schoolteacher at the Deer Park primary school at Mt. Olive Baptist Church in Woodville. She and others from Woodville still remember Preston Veal, who was called ‘Lil Pres’, since he was the namesake of Noland’s younger brother Preston. My mother to this day says he was “a smart man.” Rightfully so, as a graduate of nearby Alcorn A&M College in Lorman, Mississippi, Preston proudly came back to Woodville to teach.

Noland Veal chose to emancipate himself. As a small 5’2” tall 17-year-old enslaved on Holly Grove Plantation, he boarded a Civil War Union Navy ship with people he did not know, and travelled to places he knew nothing about. His story tells us about his desire to join in the fight for freedom and humanity for enslaved people. After the war he went back home and became a sharecropper, raised a family, and lived to see one of his son’s finish college and dedicate his life to educating the children of Woodville. May his life and his story always be remembered.

Next: A New Narrative (6/6)

Thank you for your contributions on bringing our departed ancestors to life.

Thanks Marlene.

I always learn interesting information about my family reading your blog. My great-great grandfather, Nelson Veal, also served in the Union Navy during the Civil War. Nelson’s daughter, Mary Veal, was my great grandmother. According to information on Mary’s death certificate, her father Nelson Veal and her mother Saby Cheathem Veal, were born on Greenwood Plantation. I feel proud that my Veal descendants from Bayou Sara served during the Civil War.

Thanks Gwen.

The pension files really help us bring to life our people. Nolan Veal was one of the lucky ones to get his pension and even have it raised.

Hey Kristin. Noland’s pension file has not been found yet. I was able to find his pension payment card and other military records to describe his life in the Navy.

What stood out to me like a thorn was the powerful words, “He emancipated himself”. It took grit to explore other possibilities. thank you for sharing Noland. Have you checked with the archives at Alcorn A&M College to see if they have any records of Preston – historical records, yearbooks, photos, or newsletters?

Hey Vernita. I have not found the Alcorn archives yet but I am working on it.

Great story. From slavery to education! Well done.

Thanks Denise.

Thank you for the introduction to Noland Veal. He proved that passion and purpose can push you forward.

Would other regimens like USS Gunboat refuse runaways? Or also participate in the sale of slaves? Or was it more customary that they let them in because they always needed more help?

Thanks

Shelly thanks for the questions. Black sailors, roughly 18,000 men, made up 25% of the Union Navy compared to 180,00 men (10%) of the Union army. After the fall of Vicksburg and Port Hudson many enslaved men ran off these plantations in the Mississippi Lower Valley and joined the Army and Navy. My folk in Wilkinson County ran to nearby Union Army enlistment sites along the Mississippi River — Natchez, Bayou Sara, Port Hudson, Baton Rouge, and New Orleans. Some of the boys probably lied about their age (if they even knew their age) to get onto a ship that required a minimum age of 17. One person I am researching said he couldn’t get recruited aboard a ship in Bayou Sara so he went to New Orleans and signed onto another ship. The recruiters had certain enlistment guidelines (age, size, health conditions, mental state), and quotas, that determined who was let aboard a ship. Researching and telling the story of Noland Veal has helped me understand Blacks in the Civil War Navy.